Multi-generational living arrangements often lead to some problems. Parent act like their children are still children, even if those adults are in their 20s, 40s or older. This can make life even more difficult for everyone.

Spring 2019 Multi-generational living situations

There’s an expectation when children reach a certain age, they seek independence and leave the “nest”. Today there’s a 20% chance parents find their adult children either remaining at home or returning home for a variety of reasons. Although reasons vary, these are the more common ones: Financial – credit card or school debt, loss of a job, divorce, addictions, mental health issues, or something unexpected. Different expectations often cause conflicts and difficulties among family members. In this season’s newsletter we discuss adults who have left home, only to return.

Life transitions happen to us all, at different phases of our lives. While Elder Mediation has to do with helping older adults navigate their lives, Family Conversations™ Multi-generational Living Situations focuses on older adults living with their adult children, whether they’ve never left the nest or returned for one reason or another.

Our next Newsletter – Summer 2019 will focus on helping young adults prepare for their independence. We call this Transitional Mediation. Some agencies call these Youth Transition Conferences. (link to Summer 2019 newsletter)

Multi-generational Living:

Many multi-generational living arrangements cause some problems. There’s an expectation when children reach a certain age, they seek independence and leave the “nest”. Today there’s a 20% chance parents find their adult children either remaining at home or returning home for a variety of reasons.

Although reasons vary, these are the more common ones: Financial – credit card or school debt, loss of a job, divorce, addictions, mental health issues, or something unexpected. Different expectations often cause conflicts and difficulties among family members.

Sitting down with a neutral third party helps guide the discussions, so people understand each other’s concerns. This allows for plans that benefit and satisfy everyone. We can help.

What you can do yourself, first. Here are a couple of scenarios that may be familiar to you. You have an adult child who for one reason or another hasn’t moved out yet. Or, a son or daughter has asked you, or told you, they want to move back home, or will be moving back home. What’s a parent to do?

Here are some rules and tips to consider before inviting your young adult to move back into your home. And if you think you might need some help, contact Family Conversations™. Remember these come first. Once you know yourself better, then you and your adult child can sit down to discuss the arrangement.

- Before your child moves back in – think about what this means for you

- Set some limits – for yourself and your adult child

- Have a plan of action – think things through on what you’ll do

- Consider your own needs – what do you want and need?

- Don’t get pulled into this by guilt

- Try not to react to your child’s anger

- When you’re feeling controlled by your child

- What if the relationship becomes abusive?

- When it’s time for your adult child to leave the nest

From empoweringparents.com

Adult Children Living at Home: 9 Rules to Help You Maintain Sanity

In Part 1 of “Adult Child Living at Home?” Debbie Pincus talked about the things you can—and can’t—control when your older kids move home—or when they’ve never left. In Part 2 of this hands-on series, Debbie advises parents on what to do before your child moves home, and how to handle it when the living situation isn’t working out.

What’s the golden rule of living with an adult child in the home? Clarify your expectations. This requires honest communication. Represent yourself honestly and openly as a parent. Do you expect your child to do housework, contribute to groceries and bills, and pay rent while he stays with you? How long are you willing to let him live in your home? Will he have access to your car? And what do you need to see him do in terms of job hunting, if he’s unemployed? Really think through what you want and what you’re willing to put up with, and then talk it through. If your child is to have the gift of living back home, so to speak, he also has a responsibility in the areas of courtesy, housework and possibly finances. Those are things that need to be discussed openly and honestly with your child.

The message has to be, ‘To live in this house, you need to show us that you are working towards independence. We need to see that – and you need to help yourself make that happen.

In turn, it’s important to listen to your child openly and respectfully. You have the final word as the parent but you should try to be open to your adult kid’s input. Again, your role as the parent of older kids is to be a consultant, not a manager of their lives. Listen to your child’s expectations as well. Most likely, he will feel a bit guilty or inadequate in some way. He may also feel like he’s still being treated like a child. There are all sorts of things that come up for your kids that make living with their parents uncomfortable for them.

Here are 9 rules that can guide you through this time with your adult child:

1. Before your child moves back in:

If your child is about to move back in with you, I think you need to sit down and hammer out some guidelines. Having a plan ahead of time is always good because everyone will know what to expect. Part of the conversation you’ll have with your child is, “Let’s talk about what each of us needs. What’s going to make this work the best?” Make sure everything is clear, because the living situation is all new now.

Remember, your adult kids are not coming back in as children. In a sense, they are coming home as guests. And don’t go in with the assumption that it won’t work; you’re ideally working towards collaboration. You want to be very respectful of your adult child as a participant in making decisions, but ultimately, you are the head of the house. In The Total Transformation, James Lehman talks about the four questions you should ask your child when you are anticipating some kind of change. The questions to ask (with some examples of answers you might give) are:

How will we know this is working?

“We’ll know because everyone will be doing their fair share. We’ll be respectful of each other.”

How will we know it isn’t working?

“We’ll know if someone isn’t pulling their weight or starts overstepping boundaries.”

What will we do if it’s not working?

“You will make plans to leave within a month.”

What will we do if it is working?

“We’ll continue with our original plan of six months.”

You might also ask, “What’s the goal?” Is the goal just to make a certain amount of money so your child has a cushion before he goes out on his own? Or is the goal to help him learn how to live on his own? These are all important things to establish before your child moves in. If he’s already living with you, you can still use these questions and “start fresh.” Sit down with your child and say, “Things haven’t been working out quite the way we planned. Let’s start over.”

Don’t forget to keep revisiting those conversations. From time to time, sit down and talk it through. Be sure to listen to what your child has to say and also tell him how you think things are going. You might have all the best intentions when your older child first moves in and then realize that it’s not working out the way you thought it would. Some kids don’t feel like they’re guests in their parents’ home, and that’s often where the problems start. They may have a sense of entitlement about what you should do for them and what they deserve. I think having those little conversations can be helpful. Just be clear and tell your child what your expectations are.

2. Set limits:

Be sure to set time limits and parameters on your adult child’s stay. These can be readdressed or changed around; there can be some flexibility, but be clear about the plan. And that plan might be, “You’ll stay until you get a job,” or “You’re going to stay until you get your first paycheck.” If your child is going to stay until he makes a certain amount of money, be clear and in agreement about that.

Basically what you’re helping to do is create motivation. If there’s no guide and no set time limit, there’s no motivation. You might say, “What we expect is that after six months, you’re going to have your own place.” You’re not telling them what to do; you’re making clear what you’re going to live with.

3. Have a plan of action:

Understand that helping your child get on his feet financially doesn’t mean providing everything that he needs and wants. Rather, it’s having a plan that in three months, six months, or a year, you’ll help him get an apartment, for example. You might even start out by paying a portion of his rent, but let him know that after a certain amount of time you’re going to reduce the amount you put in. That way, his responsibility grows while yours diminishes. He is working towards a goal with your help, but not relying on you completely. This is a gradual way of helping someone get on their feet. You might also tell your child that he needs to pay rent at your home. James Lehman suggests that you could consider keeping this money in a special account and then use it to help your child pay his deposit on an apartment.

Questions around finances can get complicated. Your child needs money, but how much are you willing to give? Are you giving it as a loan and expecting them to pay it back? How long do they have to do that? I don’t think there’s one right answer; I just think it has to be right for you. Consider what your finances are and what’s going to stress you too much. I think people have to figure what’s really okay with them and what’s not.

Overall, the message has to be, “To live in this house, you need to show us that you are working towards independence. We need to see that—and you need to help yourself make that happen.”

4. Consider your own needs:

Always come from a clear sense of yourself. How will you consider your needs as the adult parent who didn’t expect to have somebody back home? How can you make it work, and what are you willing to put up with? State your needs clearly and firmly to your child. As a parent, really think about what you can and can’t live with. What are your bottom lines? What are your values? What do you expect your child to adhere to if they’re living under your roof? Do you need them to pick up after themselves? Are you willing to let them have friends over and drink in your home, or not? Make sure your child knows those things and respects your rules. If he doesn’t, there’s too much room for resentments to build. You can say, “We’re going to keep open and honest communication where we both listen to each other and hear each other. There are certain responsibilities that come with the opportunity of getting to live here. I expect the house to be kept in a certain order and that if you’re coming home late you have the courtesy to call because otherwise I’ll stay up all night worrying.”

5. Don’t get pulled into guilt:

If you’ve always done everything for your child and now you’re asking him to be responsible and contribute to the household, understand that you are changing a system. You will likely get resistance and what’s called “pushback.” Your child might get very angry and say things like, “I can’t believe my own parents are doing this to me!” Don’t get pulled back in and start to feel guilty. As long as you’ve thought it through and considered your own needs and principles, you’ll be able to hold onto yourself through that anger as you insist that your child gets on his own feet.

Anytime you start to feel resentment, you have a responsibility to ask yourself, “How am I not addressing this issue and how am I stepping over my own boundaries here?” In honoring your relationships, you want to make sure that you take responsibility for what you need and what you are asking for. Otherwise you’re going to be saying “yes” to something you really want to be saying “no” to—and that’s not good for any relationship.

6. Try not to react to your child’s anger:

Try to be kind but firm and work toward being thoughtful. So rather than responding when your child says something you disagree with or that pushes your buttons, say, “You know what, let me think about what you’re saying and let’s talk later.” Don’t get pulled into that struggle. You can also say something like, “I hear you’re not happy with this and you feel like you can’t find work. I hear you saying that you don’t want to leave. Mom and Dad need some time to think about this. We’re going to discuss this and sit down and talk about this with you later.” This is one way of not getting into a battle with your child—because often times, that’s what it becomes.

I know some parents who are afraid to talk frankly with their adult kids because they don’t want to upset them or make them angry. But remember, if you’re afraid of someone’s anger, you’re never going to be willing to do what it takes. If you’re too careful because you don’t want anybody to be upset, then you won’t come across strongly enough. On the other hand, when you stop being afraid of your child’s anger, you’ll be able to stand up for yourself and let them know you mean business.

7. When you’re feeling controlled by your child:

When an older child is living at home, the situation is usually emotionally charged for everyone. Again, if you’re letting somebody control you, you’d better look at how you’re letting that happen. Ask yourself, “Am I not making clear enough boundaries? Am I not making my expectations known? Am I not making clear how long my child is allowed to stay here or how much money I’m going to give him?” If the answer to any of these questions is “no,” you need to address those issues with your child right away.

8. When the relationship becomes abusive:

I’ve worked with parents who have been verbally or even physically abused by their adult kids. When that happens, the question you need to ask yourself is, “What am I willing to live with?” Remember, as James Lehman says, “There is no excuse for abuse”—and this includes abuse from an adult child living in your home. If you feel like you’re in a dangerous situation and the abuse is scaring you in some way, seriously ask yourself, “Is it time for my child to leave altogether?” Another thing to ask is this: “If somebody’s being abusive to me, in what way am I allowing them to do that? Where am I being too passive?” You may need to say to your child, “If I’m feeling endangered here, I will need to call the police. I don’t want to do it, but I may have to.”

Again, keep your own needs—including those for respect and safety—in mind. If the verbal abuse is continuous, the discussion with your child might be, “You need to make other arrangements because it’s no longer working here. What I expect in my own home is peace and calm. If you can respect that, you’re welcome to stay. Otherwise, this is no longer going to work.”

A word of caution: don’t contribute to the problem by reacting to your child’s reactivity—this will only make things escalate. If every time you respond to your child’s anger by getting angry yourself, tuning them out, having shouting matches or getting physically abusive yourself, then you are contributing to the problem. It’s not only about what your child is doing to you—it’s also about how you’re reacting that may be adding to what’s going on. But if things have devolved into a dangerous or intolerable situation, you might decide to say, “No more. You’re out the door and you’ve got to figure it out.”

9. When it’s time for your adult child to leave the nest:

I think there are many reasons why you might decide it’s time for your child to leave. You might feel that it’s just not working or that you can’t take it anymore. Maybe your health or finances are too stressed by the situation, or perhaps you just want to be with your spouse and have that time in your life. I think it’s up to you; there’s no right answer. But the bottom line is this: When you feel that you’ve done your part responsibly, or that your child is not living up to his part of the bargain and is taking advantage of you, it may be time for him to move out.

Sit down and talk with your son or daughter if you feel things are not working out. You can say, “If you are going to stay here, I expect certain respectful behavior; otherwise you’re not welcome here. There are certain respectful ways that you live in a house with others and if that’s not possible for you, then maybe it’s time for you to leave.”

Before you ask them to leave, I think it’s very important to think about how you as the parent might be contributing to the escalation of frustration or arguments. If your child says something that makes you angry, how do you handle that anger? Do you handle it in a way that makes things worse, or better? Remember, you’re the parent. No matter how immature your child is being, you need to stay grounded; don’t go to that place. Instead, stay connected to the principles that you want to live by as a parent. And that may be to simply come back later in a mature way and say, “Look, you’re having some problems here and this is what your dad and I think.”

A final word: If your adult child is living with you or planning to move home, it might not necessarily be a bad thing. For some families, it can be a time where the relationship grows and deepens between parent and child, because you’re getting some extra time with your kids. You might be able to work out some of the difficulties that have plagued your relationships for years. So it’s not always a bad thing for adult kids to live at home. I believe the key is for everybody to understand expectations and try to work together in a cooperative, collaborative way. Be cognizant of what’s realistic on both ends. Remember, you’re not there to indulge your adult children and over-function for them. Rather, you’re helping them move towards independence and maturity. And even if there are difficulties, there is still an opportunity for the relationship to grow.

About Debbie Pincus, MS LMHC

For more than 25 years, Debbie has offered compassionate and effective therapy and coaching, helping individuals, couples and parents to heal themselves and their relationships. Debbie is the creator of the Calm Parent AM & PM™ program (which is included in The Total Transformation® Online Package) and is also the author of numerous books for young people on interpersonal relations.

Tips

Q. “My adult children are still living at home. They want to be treated as adults, but they act like kids. How can we work out this arrangement?”

A. Adult children living at home is getting more common as they remain at, or return to, their parent’s home. Often people’s expectations differ, and often aren’t even discussed. One for the first things you can do is sit down and have a conversation. Keep this in mind: Listen so your parents will talk and talk so your parents will listen. Holding a family meeting can help everyone express their wants, concerns and ways to deal with disagreements and conflicts.

Often, when families need to care for aging parents or other relatives, the burden falls disproportionately on people who live closest. It may be easier to see different solutions if you’re the one who sees the situations most often. It’s also easy for others to think they know what’s best, even if they haven’t been around too much. Sometimes people may not even agree on which issues are most important to be concerned about. Most issues are rarely black or white.

People truly want to do what helps. Trying to figure that all out may cause even more stress for family members, including the relatives you’re trying to care for.

Questions to ask yourself:

- What do I expect to give, and what do I expect in return?

- What help does my adult child want or need, and how have I determined this? Have we discussed the situation?

- Do others, spouse, relatives, friends, agree on the problems? Why, or why not?

- What are the arguments about – money, time commitments, appreciation?

Helpful Tips: Talk with siblings or other relatives and discuss your concerns. Think about having a neutral person work with you to give you feedback about what might be helpful for your situation. Get commitments to work together to, 1) take care of mom and dad (or another relative), and 2) work out family squabbles separately. Find ways for all family members to contribute to this family issue.

If you’d like more information about our mediation services, contact us for a free consultation. rich@familyconversations.com or call 952 884-1128

Millennials: The savvy, stay-at-home generation

Data shows millennials are living at home with their parents in record numbers

By Patrick Sisson Oct 10, 2017,

This story is part of a group of stories called

Property Lines is a column by Curbed senior reporter Patrick Sisson that spotlights real estate trends and hot housing markets across the country.

When 33-year-old Carolina Wong graduated from Florida State University in 2006, she had a plan. She would take her degree in advertising and her love of good design, work hard, and become a graphic designer.

The realities of the working world, and her industry, quickly altered her best-laid plans: Two years as a marketing assistant and then account executive steered her into a more marketing-oriented role, work that both “drained her soul” and wasn’t very well-paying.

Wong hit a breaking point, decided life was too short to do work she disliked, and made a move that is increasingly common among her millennial peers: She decided to move home, live with her parents, and reset. According to Pew Research Center analysis, 15 percent of 25- to 35-year-old millennials were living in their parents’ home in 2016, a much larger share than members of Generation X, born 1965 to 1979 (10 percent), and the Silent Generation, born 1925 to 1945 (8 percent), at the same age.

“I didn’t feel like I had any other option,” Wong says. She moved back with her parents in Hollywood, Florida, and ended up staying for five years, aiming to rekindle her love of film and pivot to a new career path.

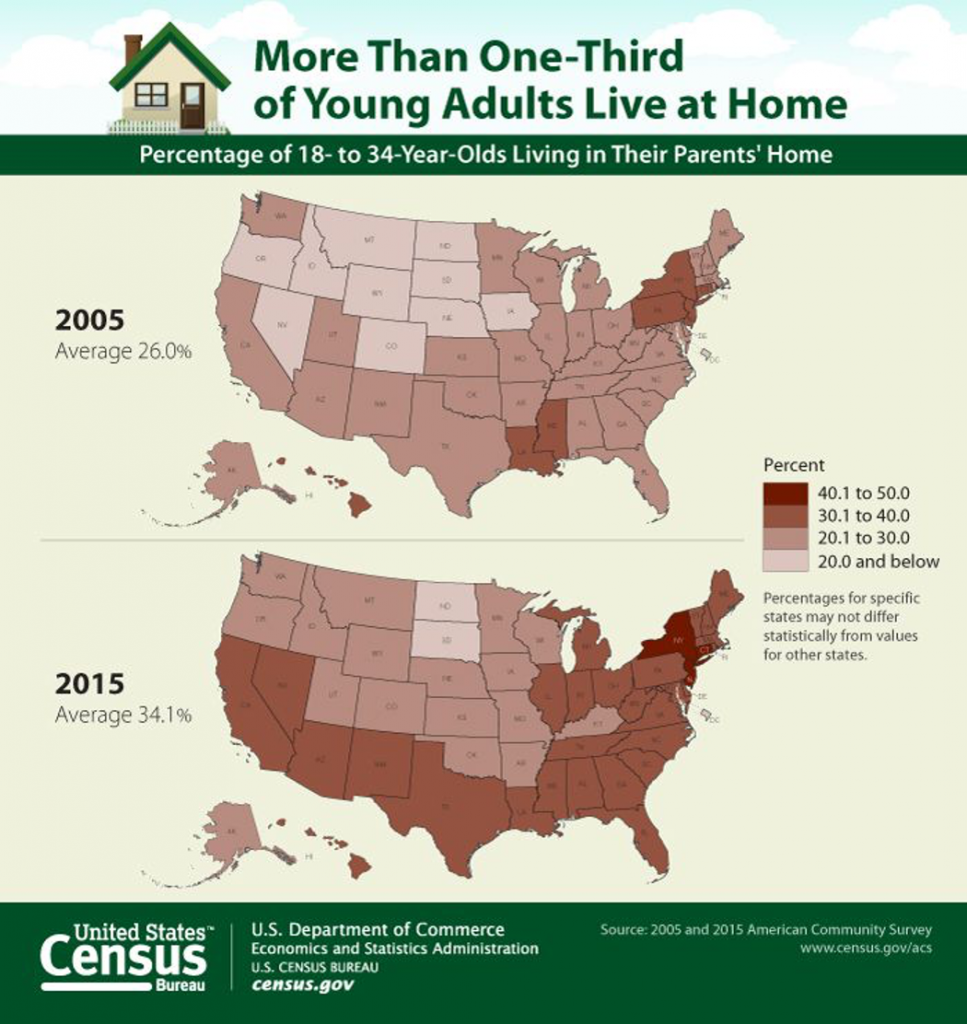

The number of young adults living at home has rapidly expanded over the last decade. U.S. Census Bureau

Wong remembers hesitating at first; despite her close relationship with her parents—which was only strengthened by moving back in—she was unsure about the move.

“That was a big struggle from me,” she says. “I didn’t want to feel like I was leeching off them. At first I dreaded it. I remember crying to my mom and discussing why I didn’t want to do it.”

Now, at age 33, Wong has a much different viewpoint after living with her parents, in many ways mirroring how social expectations and views about “boomerang” kids coming back home has shifted in just the last decade. During her time at her parents’ house, Wong was able to save enough for a down payment and buy a home, located eight miles away in Sunrise, Florida. She also parlayed experience working for local production houses on commercials into a full-fledged career as a stylist, costumer, and costume supervisor designer for film and television; after working on shows such as The Walking Dead in Georgia, she’s on the cusp of buying a second home in that state, and will soon own two homes as she navigates a more permanent move north.

Like many her age, Wong saw moving home as a route to more financial security in an increasingly insecure economic environment. She’s even counseled younger coworkers who are agonizing over making a similar choice, assuring them that it’s not a bad idea.

“If you have somebody who’s willing to help you, don’t be embarrassed by it,” she says. “I think it’s a smart decision if the help is there. There are a lot of people who don’t have that kind of help. It’s like a stepping stone; it’s not a permanent thing.”

For a generation of young adults facing the hurdles of a changing and insecure economy, there are also the barriers of rapidly rising urban housing costs and staggering loan debt (education debt alone, which has doubled since 2009, has caused a 35 percent drop in millennial homeownership, according to a New York Fed study). Add the hangover of the Great Recession and the idea of moving back home has gone from Exhibit A of this generation’s ostensible entitlement, laziness, and narcissism to something more accepted, nuanced, and less stigmatized than it was even a few years ago.

Last year, Pew research found, for the first time ever, living at home with parents had become the most common living situation for adults age 18 to 34. As census data suggests that young adults moving back home is more and more common, and many researchers believe it’s a trend that’s here to stay, it’s increasingly important to see the changes for what they represent, especially in terms of the real estate and housing markets, rather than as a sign that the kids simply aren’t alright.

“We don’t hear that stereotype of the lazy millennial discourse in the media like we did five or 10 years ago,” says Dr. Nancy Worth, a researcher at the University of Waterloo who helped compile Gen Y at Home, a 2016 study of young adults living at home in the greater Toronto area. “Now, you’re hearing how smart, strategic, and lucky young people are for staying home. It’s seen as the smart, strategic choice.”

As challenges with affordable housing and a lack of starter homes persist (inventory has plunged 40 percent since 2012), the millennial and Gen Y response—including living at home to save money and reduce debt in efforts to afford a home—can be seen as a strategic reaction to larger economic shifts.

“It’s not a reflection on the millennials; it’s a reflection of where we are as a society,” says Derrick Feldmann, a researcher who has conducted extensive studies on younger adults as part of the Millennial Impact Project.

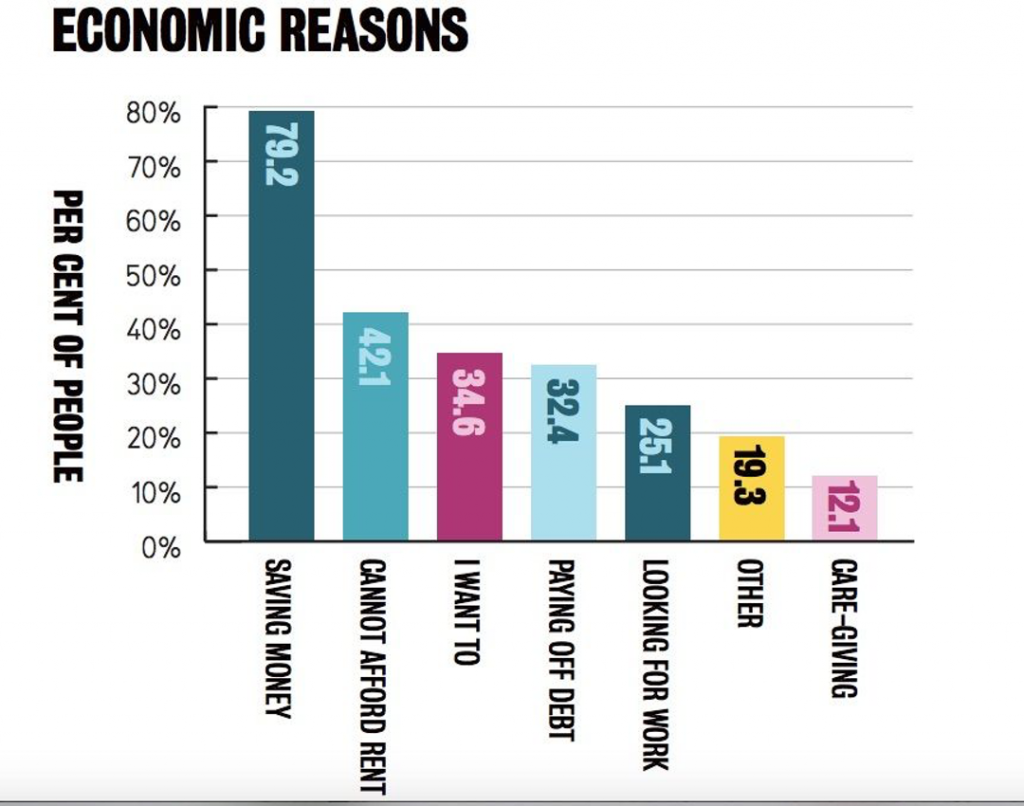

Reasons why millennials and members of Gen Y decided to live at home with their parents. Gen Y at Home

An “idle” generation that’s actually more resourceful

Feldmann’s research and marketing firm, Achieve, has spent years working on a large-scale survey of millennial attitudes about social causes and values. Overall, their research has found that millennials see themselves as more socially engaged and active than their family members. He also found that there’s more acceptance toward living with parents, in part as a recognition of economic realities.

“It was never socially acceptable for boomer parents to go into debt to go to college,” he says. “Today, it’s socially acceptable, and, in fact, boomers are the ones encouraging young adults to go through with these sorts of arrangements.”

“It’s not a reflection on the millennials; it’s a reflection of where we are as a society.”

Expectations, not surprisingly, shape how young adults view their decisions to move home. Worth says her research found that in Canadian cities—which face many of the real estate price pressures common in big U.S. cities—the combination of high rents, the difficulty in getting a down payment together to “get on the property ladder,” and the increase in part-time and contract work in the gig economy has led to a record-high number of young adults living with their parents. In Toronto, for example, 1 in 3 young adults lives at home.

“If you’re putting together a freelance career, it’s hard to sign on a dotted line when you don’t know where the money is coming from,” she says. “A report from a Canadian group called Generation Squeeze found that, to get the standard 20 percent down payment on a house, it took young people five years in 1976. Today, that’s 15 years in Toronto (and 23 in Vancouver).”

Worth says many of the respondents in her survey said that living at home “felt like a step sideways.” This wasn’t how they envisioned their late 20s or early 30s, but it’s the reality of today’s economic landscape.

Part of a larger developmental delay

Young adults are entering the workforce at a precarious time. The triple threat of high income inequality, high housing prices, and high student loans certainly comes into play, says Dr. Jean Twenge, professor of psychology at San Diego State University and author of Generation Me, iGen, and a recent Atlantic article about the impact of smartphones. But another aspect of this larger shift is more cultural and psychological. Raised with a more individualistic culture, younger adults are delaying romantic partnerships, cohabitation, and having children.

“The entire developmental pathway has slowed down,” she says. “Younger kids aren’t given as much independence and responsibility as they used to, and it’s taken longer to grow into adulthood.”

Those young adults coming after the millennial generation, whom Twenge has called iGen, is “putting off adulthood in every way.” They’re less likely to get a driver’s license, date, have sex, and drink alcohol, at the same age as previous generations. Twenge doesn’t want to make predictions as to whether the number of young adults living with parents will continue at such high rates. But she says some numbers are telling; the U.S. birthrate is showing more births among women in their later 20s than early 20s.

“That’s a fundamental shift as to when people are having children,” she says. “That’s where I’m willing to make a little more of a prediction: I believe that’s going to continue.”

With this kind of big shift, there’s a lot less stigma for a 25-year-old to live at home, since so many of their peers are doing the exact same thing.

In addition, as young-adult populations in the United States and Canada become increasingly diverse, with larger numbers of Latin Americans and South Asians, the rise in intergenerational households, and adult children living at home, is also a factor of cultural choice and cultural norms. Worth’s studies in Canada found that 1 in 3 respondents said they wanted to be at home, and there’s a lot to be said about Generation Y making that choice instead of being resigned to it.

“It’s mutual reliance; it’s a two-way back-and-forth support, for housework, errands, getting the groceries, and sharing the tasks of running a home,” she says. “You’re starting to see the beginnings of intergenerational households.”

For Carolina Wong, being closer to her Peruvian-Chinese family, and even being “protective,” of her parents, was a huge benefit.

“The very first week I was in my own house, I went home to my parents’ house every day,” she says. “It didn’t feel right. I still call the parents house home.”

She’s not the only one to feel that way. According to 2015 figures from the National Alliance of Caregiving and the AARP, millennials now make up a quarter of the 44 million caregivers in the United States, defying stereotypes of older adults taking care of each other.

Worth says that the rise in intergenerational living is a result of more than just young adults living at home. Decreasing mobility in the U.S., boomers staying in their homes instead of retiring and moving, portends a future of much more intergenerational living. Worth says that North Americans have a lot to learn from places such as Japan and Scandinavia, where co-ops and shared space are more common.

“I think it’s important to go beyond the hard data, and talk to people about how they feel about these changes,” she says.

Diversity, minorities, and the wealth gap

As statistics show the “boomerang” millennial is in fact a more common occurrence than many think, and media perception is catching up to the reality of more young adults living with their parents, perhaps another aspect of this story will get wider appreciation: the diversity—both culturally and economically—of those moving back in with their parents.

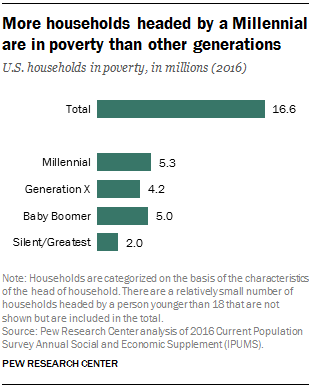

Running very contrary to the notion of millennials as a spoiled generation, Pew research notes that the number of millennial households in poverty is troublesome. In 2016, an estimated 5.3 million of the nearly 17 million U.S. households living in poverty were headed by a millennial, more than any other generation. And a majority of single-parent households were also millennials. Richard Fry, a senior researcher at the Pew Research Center, says this demographic difference is a big factor in the high number of millennials living at home: it’s not as much a failure to launch as a lack of resources keeping them away from the launch pad.

“It’s not the college-educated ones that are most likely to live at home,” he says. “It’s those who ended education with high school diplomas. It’s a disproportionately non-white, less educated part of the population. They’re doing this because they don’t have the skills and the wherewithal to live independently.”

Look at California, where 38 percent of 18- to 34-year-olds live at home (that’s 3.6 million young adults). According to research by CALmatters, a nonprofit media source, 70 percent of the 25- to 34-year-olds at home are working, and 20 percent are in school. This is not, for the most part, an idle population. But with California’s high housing costs, and median earnings for full-time working young adults in the state having dropped 11 percent since 1990, the economics of staying at home make more sense.

The collective worry found in headline portrayals of college-educated millennials returning home after school after having a hard time making it on their own obscures some serious issues of inequality, education, and job opportunities impacting a significant number of young Americans.

Fry found it was more revealing to break the demographic down by age range: 25 percent of people ages 25 to 29 live with a parent, up from 18 percent a decade ago, and 13 percent of people ages 30 to 34, up from 9 percent, with many struggling to find work, due in part to low educational attainment.

Every person’s story, and their housing decision, is an individual choice. But taken as a whole—looking at how a generation faces different economic challenges and expectations than their parents—a different narrative may emerge, one of caution, conservatism, and coming up without the same safety net.

“There’s a sense of feeling insecure about life, and not being able to know where you’ll be in five years,” Worth says about the results of her study. “It’s a sense that isn’t captured well in the numbers.”

For a free consultation contact us. rich@familyconversations.com or call 952 884-1128